History

Home » History

The history of the Teutonic Order Bailiwick of Utrecht, the organisation often known by its Dutch abbreviation, RDO, goes back more than eight centuries, to the foundation of the Order in 1190 during the Third Crusade, when the German Emperor Frederick Barbarossa summoned his knights to win back Jerusalem. The city – holy for Christians, Jews and Muslims alike – had been captured during the First Crusade (1096-1099), but lost again in 1187. A new crusade would restore it to Christian hands.

The Third Crusade

Siège of Akre | Bibliothèque Municipale de Lyon

Although Frederick drowned during the long southward journey, the crusaders eventually reached the Holy Land, where they first besieged the port town of Acre. Many of them were killed. Others lay wounded on the beach, where pity was taken on them by merchants from Bremen and Lübeck, who set up a field hospital under the sails of their ships.

The first task of the institution that developed from this was the care of sick and wounded pilgrims from the Holy Roman Empire (i.e. German Empire). Pilgrims were also able to confess to priests in their own language. Like the sick, they fell under the protection of knights, who also took a second task upon themselves: the struggle for the Holy Land.

Together, knights and priests founded a military order: The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order. Initially, this Order fought in the Holy Land. Later, to defend the Christian territories, it extended the struggle to eastern Europe, particularly Transylvania and the Baltic region.

Like the other Military Orders – the Knights Templar and the Hospitallers (Order of St. John) – the Teutonic Order was led by a Grand Master. In the Baltic region, it constituted its own state – the State of the Teutonic Order – which consisted of Prussia and Livonia, covering much of what are now Estonia, Latvia, part of Lithuania, the Russian enclave of Kaliningrad, and parts of Poland.

Outside the city walls: the land donated by Steven van Dingede | Collection of the RDO

Increases in the Order’s property

In Europe, the Order’s work was greeted with enthusiasm, and received extensive donations –particularly land, but also money – largely in the Holy Roman Empire, and also in France, Spain and southern Italy (Apulia and Sicily). The jurisdiction of the Holy Roman Empire extended far beyond present-day Germany, and also covered the Northern Netherlands. In 1231, the knight Sweder van Dingede and his wife Beatrix donated a piece of land that lay just outside the city walls of Utrecht, the purpose being to establish a house from which the knight-brethren and priest-brethren could do their work.

The primary purpose of these European properties was to help finance the Order in its campaigns for the Catholic faith. Part of the revenue went to the Grand Master. More locally, the focus lay initially on pastoral care and care for the sick, a situation that shifted towards the end of the Middle Ages, when revenues were devoted increasingly to the members’ living costs.

Grand master Konrad of Thüringen, German Master Bodo of Hohenlohe, and the Utrecht commander Anthonis van Printhagen – known as Ledersack – in worship before the cross. | Collection of the RDO

Organisationally, the Order was a pyramid, with the Grand Master at the top, the German Master below him, followed successively by the land commanders in the bailiwicks, the commanders, and the knights. A commandery was a house with a church and a landed estate; a number of commanderies made up a bailiwick, which was headed by a land commander.

Properties in the Low Countries initially fell under the authority of a magister partium inferiorum (Master of the Low Countries), who usually resided at the castle of Alden Biesen (in present-day Belgium). From the fourteenth century, the commanderies in the Northern Netherlands comprised their own bailiwick: the Bailiwick of Utrecht .

Marienburg, Prussia | Collection of the RDO

In the years around 1400, the Teutonic Order was at the height of its power, and forces arose to resist it. Now the peoples of the Baltic region had been converted to Christianity and the crusading ideal had begun to fade, Poland felt threatened. In 1410, the Grand Master’s army faced Polish-Lithuanian forces at Tannenberg (Prussia), where it suffered a crushing defeat.

Years of decline then followed. In 1457, when the Order lost its headquarters, Marienburg (now Malbork in Poland), the Grand Master transferred his administrative seat to Königsberg (now Kaliningrad). In 1525, Albert of Brandenburg, the Grand Master of the day, converted to Protestantism and created his own Duchy of Prussia out of the Order’s remaining territories, as a fief of the Polish king. As a result, Emperor Charles V passed the leadership of the Order to the German Master, whose seat was Mergentheim castle in southern Germany.

3D reconstruction of the Duitsche Huis in Utrecht as it was around 1475. | Daan Claessen, City of Utrecht Heritage Department

The “Duitsche Huis” within Utrecht’s city walls

Around the year 1400, the Bailiwick of Utrecht was also at its peak. After the devastation of the original Duitsche Huis – “Teutonic House” – by Count William IV of Holland during the siege of the city 1345, the land commandery had moved to Springweg, a street that lay within the city walls. The buildings comprised a church, a main building with chapter room, the land commander’s dwelling, and various outbuildings. In the church, Mass was celebrated by the Order’s priest.

Missaal geschonken door landcommandeur Johan van de Sande, ca. 1415 | Collection of Vereeniging voor Overijsselsch Regt en Geschiedenis, Zwolle; permanent loan to the RDO

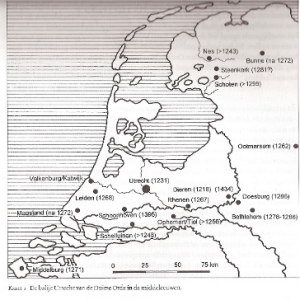

The Bailiwick of Utrecht in the fifteenth century. | Hans Mol

The Order’s properties in the Northern Netherlands, by now greatly increased, were administered from Utrecht by the land commander. Eventually, the Bailiwick of Utrecht had fifteen commanderies. And, from Utrecht, knights were dispatched to fight the enemies of Christianity, first in the Holy Land, then in the Baltic, and finally in the Balkans, where the Ottomans were advancing, a situation that lasted until the early seventeenth century.

This is when perspectives shifted. During the Eighty Years’ War (1568–1648), the enemy was the House of Habsburg, to which not only the Spanish King and German Emperor belonged, but also various Grand Masters. In the view of the States of Utrecht, the Bailiwick of Utrecht should no longer serve a Catholic Grand Master, and therefore had to become Protestant. There were no longer any priest-brethren, and, thus, by the end of a transitional period, the knights duly became Protestant and were allowed to marry. A break followed with the central Order and the Grand Master in Mergentheim. Attempts at reunification were destined to fail.

Radical changes

Caspar Anthony van Haersolte’s patents of nobility, 1762. | Collection of the RDO

The form in which the Bailiwick of Utrecht continued its activities in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was as an aristocratic institution whose wealth was administered for the benefit of its members. Potential members were put forward as children. When a space became available, the next nominee not only had to submit his patents of nobility – i.e. show that all four grandparents were nobles – but also prove his Protestant faith.

As its ranks filled with married Protestant nobles, the land commandery changed function. Its buildings were no longer a residential community. The church was no longer used, and fell into disrepair, collapsing entirely during the great storm that hit Utrecht in 1674, though the rest of the complex survived.

Every three or four years, the commanders and land commanders met in a chapter meeting. While the land commander had a residence in the Duitsche Huis, he seldom stayed there. Only the steward was always present, except when travelling to check on farmers who leased land on the Order’s estates.

New challenges arose early in the nineteenth century. After Louis Napoleon, King of Holland, had confiscated the Duitsche Huis in 1807, it became a military hospital. Four years later, his brother, Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte, dissolved the Bailiwick of Utrecht and seized its property. Although much of it was returned in 1815 after King William I had reversed Napoleon’s decree, the Duitsche Huis remained in the hands of the authorities. The Bailiwick purchased another venue for its meetings at Hofpoort, just off the Nieuwegracht.

When the military hospital was planning to move to new premises in the 1980s, the Order was given the opportunity to buy back its old house. The chapter decided to do so, but not the whole complex. Instead, it bought only the land commander’s residence, the remainder of the Order’s church, and a number of outbuildings surrounding a courtyard. The old main building and a nineteenth-century wing became Karel V, a hotel and restaurant named after the Order’s most eminent guest, Charles V, who stayed in the Duitsche Huis in 1546.

The Duitsche Huis

The Bailiwick of Utrecht resumed its use of the house in 1995, when extensive renovation work finally culminated in inaugural ceremonies. Since then, it has been the centre from which one of the Order’s oldest traditions is directed: that of helping the sick and vulnerable – an objective that became important once more in the course of the twentieth century. The order also supports research and projects that are directly related to the Order’s history and culture.

Utrecht and Vienna

Another Napoleonic decree to be reversed was the dissolution of the Teutonic Order under the Grand Master in Mergentheim, which was revived as a noble institution in Vienna, this time under the wing of the Habsburgs. After the First World War, the nature of the Order in Vienna was to change fundamentally: nobility was no longer a criterion for admission, and the Grand Master (Hochmeister) was no longer drawn from the house of Habsburg. Instead, it became a purely ecclesiastical order. Forbidden by Hitler in 1938, it was reinstated in 1945. Since 1965, the Order’s work in Germany has been supported by familiares, laypeople with a sense of involvement in charity.

Contacts between Vienna and Utrecht, which ended altogether in Napoleonic times, were re-established only recently, most notably in 2015, in a visit by then Hochmeister Bruno Platter to the land commandery in Utrecht.